By Susan Mandel

Sunday, February 3, 2008; W14

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/01/29/AR2008012904014.html

ON A CLOUDY MARCH WEEKEND IN 1902, three men trudged through the tall grass on the banks of the Potomac River. Two members of the Senate Park Commission -- Charles McKim, the nation's preeminent architect, and Augustus Saint-Gaudens, the nation's foremost sculptor -- and an aide searched for the right spot. They calculated its location, which was exactly in line with the Washington Monument and the dome of the U.S. Capitol. The men marked the area by planting a stake in the soft ground. They had determined precisely where the commission's proposed memorial to President Abraham Lincoln should be built -- on the newly filled-in marshes on the outskirts of the city, an area deserted but for bird hunters and boys looking for baby turtles in the spring. Not only would the monument create a central axis on the Mall, but it would also give Lincoln the prominent place they believed his legacy deserved.

The area was previously a bay large enough for oceangoing vessels. Erosion from farming upstream had caused a sizable buildup of soil in the river over time. By the 1880s, the river was barely a quarter-mile wide and only four or five feet deep in Georgetown. The marshes along the banks had developed the same way. Military engineers were still dumping millions of cubic yards of mud dredged from the bottom of the Potomac onto the marshes so that ships would no longer run aground. Filling in the foul-smelling Potomac Flats had its own benefits. The malaria-carrying mosquitoes that prompted wealthy residents to leave town each fall disappeared, and flooding became rare. It also extended the area between the Washington Monument and the river by nearly a mile.

Later that same day, McKim and Saint-Gaudens went to discuss their proposal with officials, including Secretary of State John Hay and Secretary of War Elihu Root. President Theodore Roosevelt had already given his support. Both Cabinet members were enthusiastic about the memorial. McKim must have felt confident as he traveled home to New York to draw up the initial plans. Little did he or anyone else at the meeting realize how controversial the proposal to build a Greek temple for the late president on the remote Potomac Flats would prove to be. This month, the nation begins celebrating the bicentennial of Lincoln's birth, including a rededication of the Lincoln Memorial on May 30, 2009. The monument has become a deeply cherished site on the Mall. McKim and the others would not have guessed that the fierce battle over their plan would carry on well after most of them were dead.

THE STORY BEHIND THE CONTENTIOUS STRUGGLE TO GET THE LINCOLN MEMORIAL BUILT can be told by piecing together information from hundreds of sources: books, memoirs, historical newspapers, academic and architectural journals, the Congressional Record, a doctoral thesis, letters and other documents.

An attempt to create a national monument honoring Lincoln in Washington two years after his assassination in 1865 had foundered. Lingering divisions over the Civil War precluded further talk of the idea until Republicans won control of the White House and both houses of Congress in 1896. The Senate Park Commission came up with its proposal in 1901 as part of a larger plan to remake the Mall.

The key obstacle was Republican Congressman Joe Cannon of Illinois, chairman of the powerful Appropriations Committee. Like his hero Lincoln, he was self-taught, having left school to support his family at age 14 when his father, a poor country doctor, drowned. He worked as a clerk at a county store for five years before saving $500 to study law. He became a successful country lawyer and then state's attorney. Cannon was able to quit work and enter politics thanks to the business acumen of his brother, with whom he'd entered a financial partnership. By 1902, he'd been in Congress 27 years and was considered one of its best debaters, despite being a self-proclaimed hayseed.

Cigar-chewing "Uncle Joe," as he was known, was an arch-conservative who believed in limited government spending. At $2 million, the Lincoln structure would be the most expensive U.S. monument ever built. (The Washington Monument, built between 1848 and 1888, cost $1.2 million.) He also had little use for anything that wasn't practical. When Congress first designated the reclaimed flats as a future park in 1897, he wanted the park to include a vegetable garden for the poor. He was guided by that same principle in matters of architecture. When Congress wanted to build new office space, he suggested putting skyscrapers atop both ends of the U.S. Capitol.

But, most of all, Cannon couldn't envision Potomac Flats as anything other than what it was. The undeveloped area was hardly a fitting place for a memorial to Lincoln, whom he'd met twice as a young man in Illinois. Its isolation, high grasses and dense brush made it a favorite haunt for vagrants. The police caught men gambling there on Sundays. Dead bodies were found in the vicinity from time to time. "So long as I live, I'll never let a memorial to Abraham Lincoln be erected in that goddamned swamp," Cannon told Elihu Root.

As Appropriations Committee chairman, Cannon was in a position to block the memorial. Prospects for it grew even more bleak when he was elected House speaker in 1903. The monument proposal had no chance of being heard with Cannon as speaker.

Still, he wasn't leaving anything to chance. At the time, the Mall was full of trees, with railroad tracks across the middle and Victorian-era buildings encroaching the borders. Turning it into a vast open green space was essential to create the sweeping view that was a key feature of the proposed monument. To make that impossible, Cannon moved to place the new Agriculture Building on the Mall. It was rumored that he threatened Agriculture Secretary James Wilson with withholding his department's funding if he didn't go along.

The American Institute of Architects, the main proponent of the Lincoln Memorial proposal, led the fight against the location for the new Agriculture Building. The group had already overcome a major hurdle when the head of the Pennsylvania Railroad agreed to move the train station that dominated the Mall to Capitol Hill. Its lobbying effort in Congress to prevent new construction on the Mall was successful in the Senate but failed in the House. But then Roosevelt intervened and ordered the Agriculture Building site to be moved just off the Mall. Roosevelt had assumed the presidency when President William McKinley was assassinated three years earlier, and he was on his way to a landslide victory in the 1904 election.

McKim thought he had finally won the chance to put the memorial on the Mall. But Secretary Wilson considered the change of site for the Agriculture Building trivial and disregarded Roosevelt's orders. Excavation for the building's foundation began on the Mall unbeknown to McKim. Wilson refused to move the building once McKim found out because $10,000 worth of work had already been done. Roosevelt agreed to a meeting with both men to settle the matter. The president listened impassively to McKim's plea, then criticized him for seeking changes after construction started. McKim thought all was lost. But the president surprised him and convinced Wilson to agree to move the Agriculture Building.Then-Secretary of War William Howard Taft congratulated McKim on his victory afterward. "He turned and looked at me a moment and said: 'Was it a victory? Another such, and I am dead.'"

Cannon drove his new electric automobile to the final Agriculture Building site on a Sunday in July 1905. The speaker, nearly 70 years old, got out of his car and hobbled to the construction area to see for himself. He climbed over the high fence surrounding the site. When he saw how far away it was from where Congress had said it should be and how large an area had already been dug for the foundation, "he said things no man really ought to say on a Sunday afternoon," according to The Washington Post.

BY 1908, A YEAR BEFORE THE 100TH ANNIVERSARY OF LINCOLN'S BIRTHDAY, even Cannon had to acknowledge that public sentiment in favor of a national memorial to the late president was too strong to be ignored. So he backed a proposal to place a memorial near the new Union Station. No place was more convenient. Visitors arriving by train would see it without going out of their way, whereas they'd have to make a special trip by streetcar or carriage to the Potomac River location. Cannon said from the beginning that he wanted the monument located "where all who visit Washington would see it without expense."

The Union Station proposal was part of a bill to expand the Capitol grounds by purchasing the six blocks between the Capitol and the station. A monument to Lincoln would fit nicely somewhere in between, Cannon told the Washington Star. It only made sense for the government to acquire the land. The Irish slum that occupied the area was hardly a dignified approach to Congress. Nicknamed Swampoodle because of its marshy land near Tiber Creek, it was a mix of shanties, run-down buildings and alleys where many of the Irish laborers lived in crowded tenements. Schott's Alley, next door to the new Russell Senate Office Building, was home to 220 people, most of them fruit vendors. On one shack that housed a restaurant, the owner regularly painted his comments about current events on the outside walls.

The city's alley slums were notorious. The dilapidated brick or wood dwellings -- built to house emancipated slaves after the Civil War -- had dirt floors and typically lacked sewers, water, heat and light. Two families often shared four small rooms. A local doctor who took congressmen on tours of the alleys near the Capitol to motivate them to clean up the unsanitary conditions had a dramatic way of making his point. He'd open up an outhouse door and say, "Gentlemen, these flies are the same ones that come in your open window and land on your sandwich while you're having lunch on Capitol Hill," according to photographer Godfrey Frankel's book In the Alleys: Kids in the Shadow of the Capitol.

Cannon's effort to beautify the area around Union Station marked a total reversal of an earlier position. He'd tried to eliminate the 1,000-foot-long plaza in front of the train depot, calling it an unnecessary extravagance when the House approved the plan in December 1902. "Would it not be more harmonious still if we should make the plaza include 10 acres and . . . clean out all the buildings between the Capitol and the depot?" he sarcastically asked during the debate. His objection to the plaza was the only opposition to the bill to create Union Station. But now that the train depot had opened, Cannon agreed with the popular sentiment in Congress that such a slum-clearance project was exactly what was needed.

Former congressman James McCleary soon published a magazine article with a new idea for memorializing Lincoln that received considerable attention. He had been a member of the Lincoln Memorial Commission authorized by Congress in 1902, before Cannon was House speaker. At the group's one and only meeting, the members decided to send McCleary to Europe to study its monuments, as McKim and the other Senate Park Commission members had already done. McCleary went abroad but still hadn't submitted his report to the commission three years after it was due. The commission was basically defunct by that time anyway because its members didn't want to do anything that would anger Cannon.

What had most impressed McCleary during his tour of Europe was the Appian Way, the ancient road in southern Italy built by Roman censor Appius Claudius. "Who has not heard of the Appian Way?" he wrote in the article. "What a fitting memorial to Lincoln would be a noble highway, a splendid boulevard, from the White House to Gettysburg."

"The Lincoln Way" would include one roadway for automobiles and one for horse-drawn carriages and wagons; plus two electric railway tracks: one for express trains, the other for local trains. Stately rows of trees would border the highway. Down the middle would be a well-kept lawn 40 to 50 feet wide, with beautiful fountains and monuments at intervals along the way. Given "the possibilities of electrical illumination, the beauty of this boulevard when lit up at night may be left to the imagination," McCleary wrote.

He wasn't the first to think of combining a memorial to a great American with some practical purpose. In 1882, there was serious talk of putting a weather station at the top of the Washington Monument once it was completed.

But, with widespread support in Congress, the proposed Lincoln Memorial near Union Station seemed certain to win quick approval. Cannon confidently told newspapers that he planned to have the bill passed and ready for Roosevelt to sign on the upcoming Lincoln centennial February 12, 1909.

McKim was in poor health by then. So, Glenn Brown, secretary of the American Institute of Architects, took over advocating for a memorial near the Potomac River. He was from a distinguished old Southern family. His background was similar to that of his elite clientele. But his modest, gentlemanly demeanor belied his tenacity and shrewd political skills. He was determined to stop the Lincoln Memorial from being built near Union Station, where it would be overshadowed by the station and the Capitol building and obstruct the view. Besides, a statue of Christopher Columbus was already planned for the most prominent spot in front of the station.

It's ironic that Brown grew up admiring Robert E. Lee more than he did Abraham Lincoln. His father, a physician, had been a field surgeon in the Confederate Army and later inspector of hospitals and camps. Brown used to sneak over to the slaves' cabins as a boy to teach them to read. One day, he saw his grandfather standing on the back porch and telling the 150 slaves on his 1,000-acre North Carolina plantation that they were free, plunging the family into financial ruin.

With just days before the House was expected to approve Cannon's memorial near Union Station, Brown and three of his colleagues went to Roosevelt and asked him to create an expert panel to advise him on all new federal buildings, monuments and works of art. It had been a long-term goal of Brown's, who was hardly alone in considering much of the public art in Washington mediocre. One congressman suggested the commission take broadaxes and go on a tour of the city "smashing half the so-called works of art," a newspaper article said. But Brown then saw the advisory body as his only hope for thwarting the competing memorial proposal.

Roosevelt paced up and down the Red Room of the White House as he listened to the architects late one Sunday night, according to accounts by Brown and American Institute of Architects President Cass Gilbert, who accompanied him.

"Mr. President, the proposition to belittle the dignity of Lincoln by making his memorial an ornament and part of the railway station shows the need of expert advice," Brown pointed out. "Isn't the station a good place for it?" the president asked. "They tell me it is all right."

After Brown explained his objections, Roosevelt turned to his trusted aide Gifford Pinchot, who would become head of the U.S. Forest Service, and said, "Giff, I'm going to do what these men want."

Roosevelt told Brown that "Congress will . . . become indignant and say I am exceeding my authority, but I consider it my right and duty to secure expert advisers when I need them. The more violent the congressional objection, the more publicity the papers will give the subject." Roosevelt knew that would generate public support for the commission. "Congress will listen to the public demands." He understood the value of publicity better than anyone else of his era. His remarkable ability to use the press for his own aims had propelled his rise to the Oval Office.

In January 1909, near the end of his term, the president established the Council of Fine Arts and asked it to immediately take up the question of the Lincoln Memorial. The council -- made up of architects, painters and sculptors -- unanimously ruled in favor of the site by the Potomac River. Infuriated, Cannon responded by inserting a provision revoking the council's authority in a government funding bill. Roosevelt signed the bill on his last day in office, but he attached a note declaring the provision on the Council of Fine Arts unconstitutional and therefore not binding on any president.

The furor in Congress produced the favorable press and public support that Roosevelt had predicted. Public opinion turned against putting the memorial near the train station. Backers of that proposal were forced to retreat.

Roosevelt's successor, President William Taft, also favored the proposed Lincoln Memorial near the river. He disbanded the Council of Fine Arts in 1909 and named one of the authors of that plan, Daniel Burnham, chairman of the new Commission of Fine Arts the following year. This new commission, created by Congress, merely advised on local fountains, statues and monuments and had no legal authority. Burnham, who ran the most profitable architecture firm in the country, had been on the now-defunct Senate Park Commission with McKim and Saint-Gaudens, both of whom had died by now.

Around the same time, a group of insurgent Republican congressmen unhappy with Cannon's dictatorial rule led a revolt against their party leader. Nebraska Congressman George Norris cleverly seized on a parliamentary ruling Cannon had made to introduce a bill to remove him as chairman of the Rules Committee, through which the speaker determined the schedule of business, recognized members to speak, made all committee appointments and thus controlled every aspect of House activity. A constituent once asked for a copy of the House rules, and his congressman simply sent him a picture of Cannon.

Cannon and his allies launched a filibuster to stall for time so they could round up enough votes to rescue him. His lieutenants made calls and sent telegrams to absent Republican supporters to ask them to return to vote. Word of the long-awaited showdown quickly spread, and the galleries filled with spectators. The speaker listened quietly for hours as his critics enumerated his alleged crimes and his defenders praised him. Decorum broke down as the debate wore on into the night with members jeering and yelling insults at one another and Cannon. The speaker broke his gavel from banging it all night. By morning, it was apparent that Cannon couldn't get enough votes to win. His friends pleaded with him to step aside for the good of the party. But he refused.

The two Republican factions tried to negotiate a compromise, but their efforts proved fruitless. The speaker finally ended his 26-hour filibuster at 4 p.m., knowing he faced defeat when the measure to throw him off the Rules Committee was voted on the next day. The 74-year-old Cannon was still full of energy and fresh-looking. "Boys, it looks as though we're beaten, but we'll die game," he said to his allies, according to a biography of George Norris.

As the votes went against him, Cannon remained cool and dignified. Afterward, he promptly asked to address the House. He said he wouldn't resign because he'd done nothing wrong. Then he stunned everyone by inviting a vote to remove him as speaker. He knew that the Republican insurgents would vote to keep him to avoid having a Democrat become speaker. Cannon won that vote. His supporters cheered wildly and rushed to congratulate him. He managed to make his defeat look like a great victory. But the biggest obstacle keeping Congress from even considering the proposed Lincoln Memorial in Potomac Park, as the area was now called, was gone. That fall, winning its approval became urgent. In midterm elections, the Republicans lost control of the House for the first time in 16 years, and Southern Democratic leaders had little interest in a memorial to Lincoln.

With the Democrats set to take control in March, Brown got Sen. Shelby Cullom of Illinois to introduce a bill to establish a commission to create a memorial. The 81-year-old senator had been a family friend of Lincoln's. He had warned Lincoln about rumors that he was in physical danger, but Lincoln said he would have to take his chances, Cullom later wrote in his memoir. Three weeks later, Cullom accompanied the president's body back to Springfield, Ill., for burial. His bill to create a memorial finally became law in February 1911, one month before the new Congress convened.

BUT THIS WAS ONLY PHASE ONE OF THE BATTLE. As a member of the new Lincoln Memorial Commission, Cannon still aimed to block the Potomac Park location. He secretly persuaded a majority of his fellow commission members to vote for a new location at Arlington National Cemetery, the former home of Robert E. Lee and where Union soldiers were buried. Commission of Fine Arts member Frank Millet, who would soon die onboard the Titanic, happened to overhear talk about Cannon's plan the night before the memorial commission meeting. There was no time to warn Taft, who chaired the commission. So Millet had his friend Texas Congressman James Slayden convince one of the panel's Southern members that Arlington was unsuitable.

When the memorial commission met the following morning in the White House executive office, Cannon argued against the Potomac Park site, calling it a swamp and saying that "the memorial would shake itself down with ague and loneliness." He then made a stirring plea to put the memorial to Lincoln alongside his fallen troops in Arlington. House Speaker Champ Clark of Missouri sat quietly. When it was his turn to speak, he stretched his long legs under the table and said, "I, for one, will never consent to the erection of the Lincoln Memorial in any part of the South. We should not imitate the custom of the ancient Romans by placing a memorial of the conqueror in the territory of the conquered," repeating just what the Texas congressman had said to him.

Taft quickly realized that Cannon's new scheme had been quashed. "Well, Uncle Joe, I guess you and I will have to give up Arlington!" said the president, a genial man who hid his dislike for Cannon.

The question of the memorial's location was still unsettled at the end of the meeting. Cannon kept pushing for other locations. When the Fine Arts Commission recommended McKim's former assistant, Henry Bacon, as the architect, Cannon opposed him, too. He persuaded the memorial commission to have Bacon and architect John Russell Pope compete for the job. While Bacon drew up plans for Potomac Park, Pope made plans for Cannon's new favored sites: the Soldiers' Home in Northwest Washington, where Lincoln had his summer cottage, and Meridian Hill on 16th Street, north of the White House. Models of the architects' plans for three locations were placed on exhibit at the new National Museum (now the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History). Cannon wasn't the only one trying to undermine the commission's recent recommendation. Proponents of the Lincoln Memorial highway launched a national campaign to get Congress to approve the road to Gettysburg instead. The commission wasn't allowed to consider anything outside of Washington, but Taft met with them anyway.

Speaker Clark joined the growing number of highway supporters, telling the Washington Star that "Lincoln was a practical man; a great man, with practical ideas. If we are to expend that much money, we should expend it where it will do some good, and the most good that can be done is by building a great highway from Washington to Gettysburg."

There were no decent roads to Washington or to most towns. Rural America's dirt roads were the worst in the developed world. Fifteen years after the first automobile appeared in the nation's capital in 1897, few people owned cars because of the cost. The $1,200 average price of a car in 1912 is equivalent to about $26,000 today. But their numbers were growing, and the country's miserable roads became a political issue. John Stewart, president of the International League for Highway Improvement, was quoted in a 1912 New York Times article as estimating that the cost to build adequate roads throughout the country would be at least $25 billion.

The memorial commission finally approved Bacon's modernized version of an ancient Greek temple on the Mall in December 1912. Cannon had lost his reelection bid the previous month in the Democratic sweep that would bring Woodrow Wilson into the White House three months later.

The Senate quickly adopted the panel's recommendation of a Greek-style temple, but it still faced an uphill battle in the House. Rep. William Borland, the Missouri congressman who led the highway effort, predicted an easy win for the road. He believed cars would become more popular, though he didn't drive one himself. Many congressmen found the prospect of obtaining federal dollars for road projects in their own districts tempting. Road supporters, backed by the auto industry, were well-organized. They flooded Congress with telegrams and petitions. Architect Glenn Brown's campaign in favor of a Greek temple was no match. Everyone knew that a House victory for the Lincoln highway would create a stalemate and indefinitely postpone the creation of any memorial because the Senate wouldn't agree to the road.

Brown organized a meeting of local memorial supporters just before the vote. Sen. Elihu Root of New York launched a searing attack at the meeting that made front-page headlines. He'd learned that a group of speculators in Washington had obtained options on the land where the Lincoln highway would run. "A cabal is at work to defeat this Lincoln Memorial plan," he charged, in order to build a road as part of a scheme to boost property values in the area, according to newspaper accounts.

Tensions were high when the memorial resolution was debated the following week. House members wore carnations in their lapels in memory of Lincoln. Brown sat in the gallery alongside Bacon.

Highway advocates attacked the memorial plan as foreign and not representative of Lincoln, according to the Congressional Record. "There is nothing in this Greek temple . . . that even suggests . . . the character . . . of Abraham Lincoln," said Rep. Isaac Sherwood of Ohio. "It is time we had some American art and . . . American ideas in this national capital."

A highway is "nearer to expressing the epoch of American history than any other form of memorial," said Borland, who emphasized that a road was unanimously endorsed by the Grand Army of the Republic, whose members were Union veterans. The Greek temple is the most hackneyed form of architecture known, he added. Another called the memorial "utterly useless."

Rep. Samuel McCall of Massachusetts, defended its design, saying: "There is nothing more beautiful in architecture than the column of the Greek . . . It illustrates dignity, beauty, simplicity and strength," all qualities that Lincoln represented.

Knowing that aesthetic arguments weren't likely to sway members, Brown had prepared a cost estimate for the Lincoln highway, which Rep. Lynden Evans of Illinois used effectively during the debate. "It will cost at least $20 million to build a really distinctive road," he said, and pointed out that it could be used only by those who could afford a car. "If a trolley line was placed upon it so that the plain people could use it, it would be valuable and useful . . . But it would not be a memorial of Abraham Lincoln."

Other members accused Lincoln highway supporters of being more concerned about roads than honoring Lincoln. The fundraising letter stated that the road would become the nucleus of a national highway system, Rep. John Stephens of Texas noted, warning that "it would be an entering wedge for the appropriation of hundreds of millions for public roads."

At one point, Rep. Henry Cooper of Wisconsin rushed onto the floor waving a telegram and asked to be heard. He said he'd just received the telegram from an official of the Grand Army and that the group had endorsed the memorial in Potomac Park, contrary to Borland's claim. The news caused some commotion.

After five hours of debate, the opposition collapsed. Many road advocates ended up not voting. Brown's cost estimate turned out to be the fatal blow. Other members had proposals of their own. But Bacon's memorial was their second choice. It passed the House overwhelmingly. The chamber erupted in applause. Shelby Cullom, Lincoln's friend, wept with joy. An agreement to build the Lincoln Memorial had finally been reached more than 10 years after Charles McKim drove a stake in the ground marking the spot along the Potomac River where it would stand.

CANNON RETURNED TO CONGRESS IN 1915. Not long after, Brown ran into him on a streetcar and sat down next to him. He congratulated Cannon on his reelection and then asked how he liked the Lincoln Memorial now that it was taking shape.

"I have been in many fights -- some I have lost, many I have won. It may have been better if I had lost more," Cannon replied, according to Brown's memoir. "I am pleased I lost the one against the Lincoln Memorial." Cannon went on the House floor later and publicly acknowledged that he was wrong to have ever opposed the monument.

"We tenderfeet . . . perhaps ought not to have our way in matters of art," he conceded. "Looking through hindsight, I am inclined to think the Art Commission and the majority of the Memorial Commission located this memorial where it ought to be located."

Susan Mandel is a freelance journalist in Arlington. She can be reached at susantamara@yahoo.com.

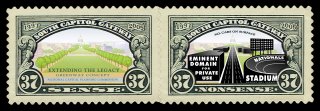

2005 NCPC study

2005 NCPC study