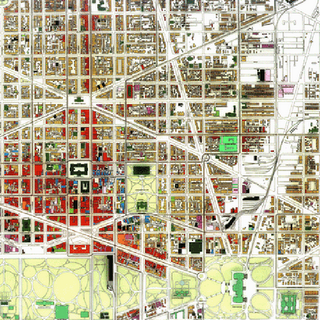

Illustration : The L'Enfant Plan downtown Washington, D.C. in 1860, prior to the introduction of urban railroads (note the open creek along Deleware Avenue NE)

Illustration : The L'Enfant Plan downtown Washington, D.C. in 1860, prior to the introduction of urban railroads (note the open creek along Deleware Avenue NE)Illustration: The L'Enfant Plan downtown Washington, D.C. in 1900, with urban railroads

1863: To conform with evolving transportation infrastructure needs, the B&O RR is constructed through D.C., along a route through NE that covered over the existing creek, and a north-south segment across the National Mall in a depressed open cut.

Although the idea of a tunnel would seem to be elementary, people actually debated even allowing a RR to pass through an urban core: a mid 1800s debate evident in the current display in the basement of the U.S. Capitol building.

This RR started construction in 1863, and was routed from the north via 1st Street NE and Deleware Avenue, that would cover over the creek. It included a station directly inside the National Mall. This was the location of the assassination of US President Garfield in 1882.

Illustration: The L'Enfant-McMillan Commision Plan downtown Washington, D.C. in 1940, with modified urban railroads

1901: The McMillan Commission: established via new landfill, the western extension of the National Mall with the Reflecting Pool and the Lincoln Memorial and Traffic Circle, which was completed in 1922. It also conformed with transportation infrastructure needs, but with reconstructions making it more friendly for the adjoining areas down-town, replacing the B&O segment across the Mall with a tunnel starting at a new Beaux Arts Union Station and running beneath 1st Street NE/SE, emerging at C Street SE.

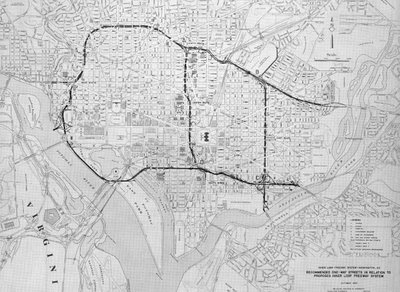

Illustration: The 1955 Inner Loop Engineering Study Plan downtown Washington, D.C.

1955 Inner

It placed the SW Freeway north of the G Street SW site lines to the Jefferson Memorial

Construction started on the I-95 (now I-395) SW Freeway by 1959, along with its connections to the George Mason Bridge which crosses the Potomac River, and completed in 1962.

Construction started on the I-66 Theodore Roosevelt Bridge by 1957, followed by its connecting I-66 West Leg by the JFK Center to the vicinity of K Street from 1963-1966.

Construction continued on the SE Freeway and its connecting 11th Street Bridges through 1963-1966. This followed the cancellation of the initial plan for the East Leg along 11th Street NE/SE, and its replacement with an East Leg route along the west/north shore of the Anacostia River to what became RFK Stadium, before turning northwesterly, around 1962. Construction of the easternmost portion of the SE Freeway, including the pair of underpasses beneath Barney Circle, between 1967-1974, anticipated this extension, as attested by the space for 4 lanes per direction. However, this extension was cancelled in the late 1970s.

It's adoptation of a cut and cover tunnel with a straight alignment, replaces the 1955 Inner Loop study's options for either a straight alignment open cut depressed configuration, or a curved alignment cut and cover tunnel. The curve was meant to spare a group of trees. Under a 1965 inter-government-agency agreement, the straight tunnel was adopted as less expensive then a curved tunnel, with the cost savings going for replacement trees and the reflecting pool that was subsequently constructed atop.

Illustration: 1970 downtown Washington, D.C. with I-95 Center Leg to Massachusetts Avenue

Illustration: 1970 downtown Washington, D.C. with I-95 Center Leg to Massachusetts Avenue

1971 D.C. Freeway Re-design:

Illustration: From Scott Kozel's www.roadstothefuture.com

http://www.roadstothefuture.com/DC_Interstate_Map.html

Construction of the northern extension of the Inner Loop's middle north-south segment, the Center Leg (3rd Street Tunnel) to New York Avenue, with a cut and cover tunnel between Massachusetts Avenue and K Street, started in 1978, with the basic 1971 design intended to accommodate the I-66 K Street Tunnel, and an effective further continuation of the Center Leg via an I-95 (or I-395) North Leg East segment to the north-east.

Its alignment features a north-westerly curve to accommodate preserving the

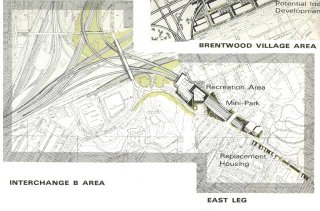

Illustration: 1971 Deluew-Cather-Weese Associates downtown Washington, D.C. with I-66 Pennsylvannia Avenue-K Street-New York Avenue Tunnel, and I-95 North Leg East, with northern end of I-95 (I-395) Center Leg (built 1978-1982) at right

Illustration: 1971 Deluew-Cather-Weese Associates with I-295 East Leg Mt. Olivett Road Tunnel

http://www.highwaysandcommunities.com/1971_I-70S_I-95_NCF_NEF_Revisted.htm

The K Street Tunnel was the later concept for a cross-town (east-west) I-66 with minimal building displacement or bisection.

Although more expensive per lane mileage, its shorter distance and its minimal footprint (and hence its preservation of the existing building stock and their tax revenue) gave the I-66 K Street Tunnel good economics (even with accounts failing to see its potential for brown fields redevelopment along the

The I-66 K Street Tunnel concept was promoted by NCPC's Elizabeth Rowe in the mid 1960s, though she would turn against it by November 1973 with the arguments that the then current gasoline shortages would mean that the very concept of private automobiles would be obsolete by the 1990s.

In the 1971 design (above) it takes no buildings, because for most of its length, it ran entirely under existing public right of way, with the exception being along the northern side of

Both the I-66 K Street Tunnel and the existing I-95 (I-395) Center Leg required the North Leg East segment of the Inner Loop, in order to connect with the B&O RR to the north and the New York Avenue RR corridor to the east, with sufficient adjacent space to construct main highways with comparatively little or no displacement of dwellings. In the 1971 design (above), the North Leg East segment was a 10 lane cut and cover tunnel along the northern side of

This marked the completion of only the lower inverted "T" of the basic Inner Loop schematic.

Illustration: Barney Circle Bridge Underpass

In the years since, DC pursued only one freeway extension project at a time, the Barney Circle Bridge Connector Project, initiated in 1983 and cancelled in 1996.

Illustration: 1996 D.C. Mayor's Office "Ron Linton" I-395 New York Avenue Tunnel

Afterwards, official planning has persued a New York Avenue project with a tunneled extension of I-395 directly beneath. This has the advantage of avoiding any building displacement, but with the trade off of poor geometry with its curved transition from existing I-395 immediately behind the Bibleway Church complex located on the west side of New Jersey Avenue.Neither the Barney Circle Bridge Project, or the New York Avenue projects appears in National Capital Planning Commission planning.

http://www.roadstothefuture.com/DC_Interstate_Fwy.html

An excellent source of the square cropped images above from:

http://www.passonneau.com/pages/maps.html

No comments:

Post a Comment